Architecture#

This page has information about the different architectural designs of core pieces in the Jupyter ecosystem. Some of these are individual projects, and others show the relationships between projects.

Projects overview#

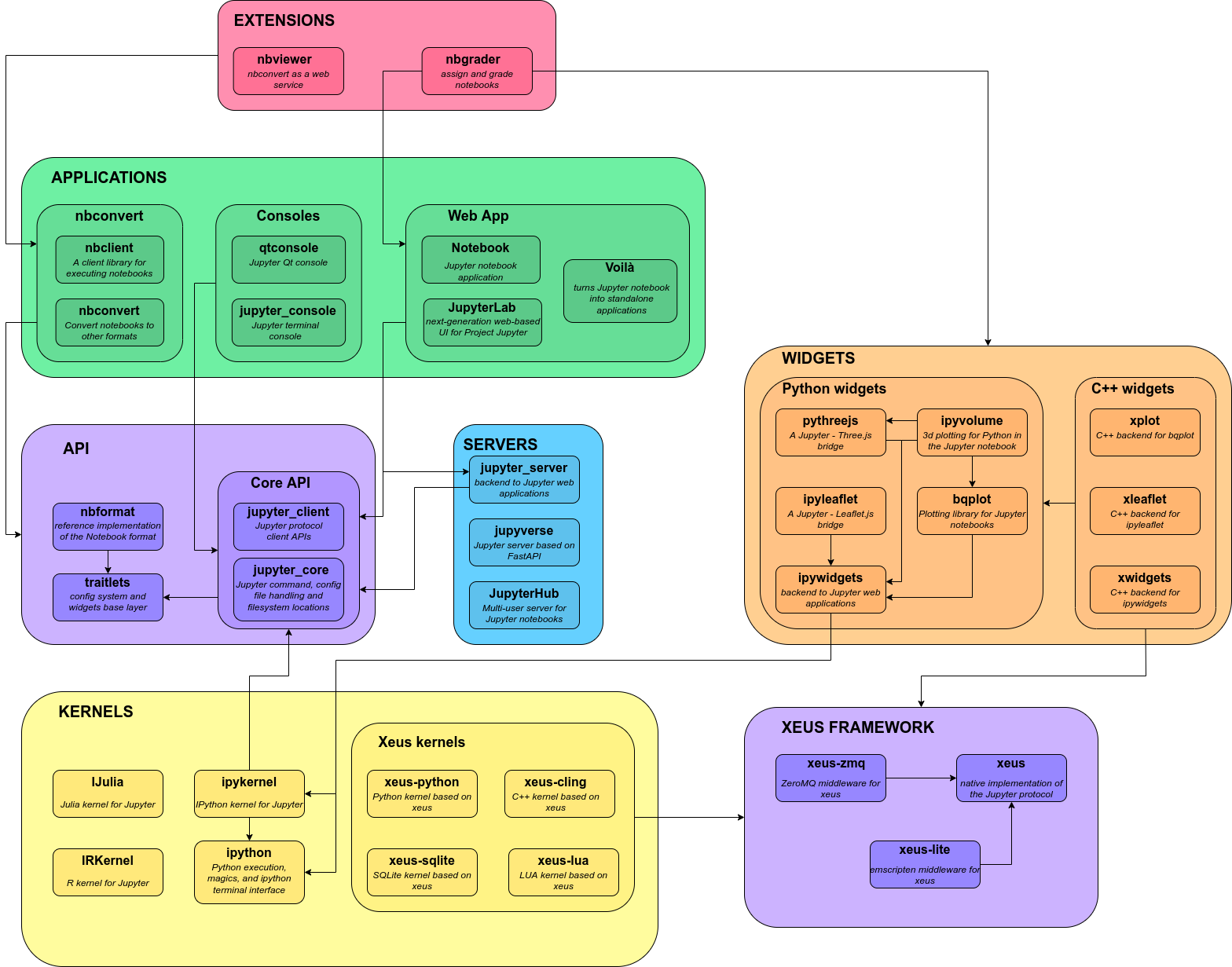

Below is a high level visual overview of project relationships. It is current as of 2022.

IPython Kernel#

This section focuses on IPython and kernels.

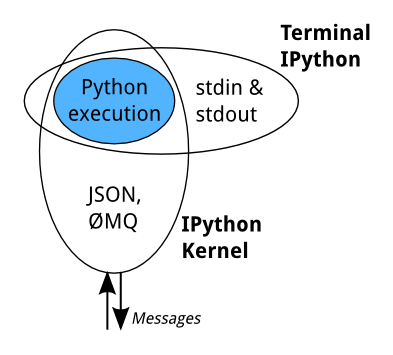

When we discuss IPython, we talk about two fundamental roles:

Terminal IPython as the familiar REPL

The IPython kernel,

IPykernelthat provides computation and communication with the frontend interfaces, like the notebook

Terminal IPython#

When you type ipython, you get the original IPython interface, running in

the terminal. It does something like this:

while True:

code = input(">>> ")

exec(code)

Of course, it’s much more complex, because it has to deal with multi-line

code, tab completion using readline, magic commands, and so on. But the

model is like code example: prompt the user for some code, and when they’ve

entered it, execute it in the same process. This model is often called a

REPL, or Read-Eval-Print-Loop.

The IPython Kernel#

All the other interfaces —- the Notebook, the Qt console, ipython console

in the terminal, and third party interfaces —- use the IPython Kernel. IPykernel

is a separate process which is responsible for running user code, and things

like computing possible completions. Frontends, like the notebook or the Qt

console, communicate with the IPython Kernel using JSON messages sent over

ZeroMQ sockets; the protocol used between the frontends

and the IPython Kernel is described in Messaging in Jupyter.

The core execution machinery for the kernel is shared with terminal IPython.

A kernel process can be connected to more than one frontend simultaneously. In this case, the different frontends will have access to the same variables.

This design was intended to allow easy development of different frontends based on the same kernel, but it also made it possible to support new languages in the same frontends, by developing kernels in those languages, and we are refining IPython to make that more practical.

Today, there are three ways to develop a kernel for another language:

Wrapper kernels reuse the communications machinery from IPykernel, and implement only the core execution part.

Native kernels implement execution and communications in the target language.

Kernels based on xeus, a native implementation of the protocol, implement the language-specific part of the kernels. Contrary to the wrapper approach, xeus does not depend on a python runtime.

Wrapper kernels are easier to write quickly for languages that have good Python wrappers, like octave_kernel, or languages where it’s impractical to implement the communications machinery, like bash_kernel. Native kernels are likely to be better maintained by the community using them, like IJulia or IHaskell. Xeus kernels are easy to write when the language interpreter provides a C++ or a C API.

The Jupyter Notebook format#

Jupyter Notebooks are structured data that represent your code, metadata, content,

and outputs. When saved to disk, the notebook uses the extension .ipynb, and

uses a JSON structure. For more information about the notebook format structure

and specification, see the nbformat documentation.

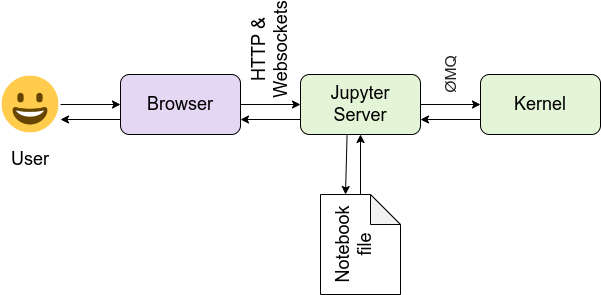

The Jupyter Notebook Interface#

Jupyter Notebook and its flexible interface extends the notebook beyond code

to visualization, multimedia, collaboration, and more. In addition to running your code,

it stores code and output, together with markdown notes, in an editable

document called a notebook. When you save it, this is sent from your browser

to the Jupyter server, which saves it on disk as a JSON file with a

.ipynb extension.

The Jupyter server is a communication hub. The browser, notebook file on disk, and kernel cannot talk to each other directly. They communicate through the Jupyter server. The Jupyter server, not the kernel, is responsible for saving and loading notebooks, so you can edit notebooks even if you don’t have the kernel for that language—you just won’t be able to run code. The kernel doesn’t know anything about the notebook document: it just gets sent cells of code to execute when the user runs them.

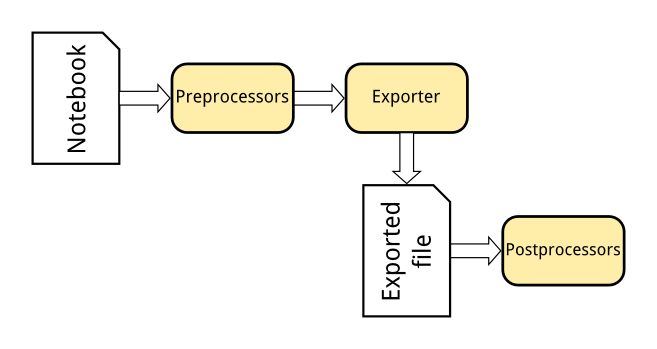

Exporting Jupyter Notebooks to other formats#

The Nbconvert tool in Jupyter converts notebook files to other formats, such as HTML, LaTeX, or reStructuredText. This conversion goes through a series of steps:

Preprocessors modify the notebook in memory. E.g. ExecutePreprocessor runs the code in the notebook and updates the output.

An exporter converts the notebook to another file format. Most of the exporters use templates for this.

Postprocessors work on the file produced by exporting.

The nbviewer website uses nbconvert with the HTML exporter. When you give it a URL, it fetches the notebook from that URL, converts it to HTML, and serves that HTML to you.

IPython.parallel#

IPython also includes a parallel computing framework, IPython.parallel. This allows you to control many individual engines, which are an extended version of the IPython kernel described above.

JupyterHub and Binder#

JupyterHub is a multi-user Hub that spawns, manages, and proxies multiple instances of the single-user Jupyter notebook server. This can be used to serve a variety of interfaces and environments, and can be run on many kinds of infrastructure. JupyterHub on Kubernetes is a Helm Chart for running JupyterHub on kubernetes infrastructure, and BinderHub is a customized JupyterHub deployment for shareable, reproducible interactive computing environments.

The links below describe the architecture of JupyterHub and several distributions of JupyterHub.

JupyterLab#

JupyterLab is a flexible, extensible interface for interactive computing. Below are a few links that are useful for understanding the JupyterLab architecture.